Demystifying Digital Assets articles

Date

23 Jun 2022

Related Expertise

In our modern world, the acquisition and use of digital assets such as cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (‘NFTs’) (collectively ‘crypto’) is becoming increasingly common. Many would argue their adoption is growing exponentially.

This paper, and its related presentation, intends to be practical in its focus. The aim is to demystify the uncertainty around these assets generally and particularly in a relationship property context, including:

- What exactly are crypto? What might a portfolio look like? And how and why might it be acquired, used and held, and why it is important that we understand this? [1]

- How is crypto classified in a relationship property situation?

- What suggestions are there for identifying crypto-assets if disclosure is not forthcoming?

- How do you ascertain their value?

- How can or should such assets be protected during a relationship, how and when can or should they be divided on separation, and what should be considered in terms of asset / estate planning?

- Practical tips, resources and professionals who can provide practitioners with insight and assistance in this area.

Why Should Lawyers Care About Crypto Assets?

Digital assets are rapidly becoming commonplace. As we move towards a more online society, with the growth of the ‘metaverse’ and ‘Web3’ fast-tracked by a global pandemic, lawyers should expect to encounter increasing numbers of clients seeking advice on digital assets across a range of practice areas.

Given the rising presence of crypto within investors’ portfolios, and the shift in business, lawyers will inevitably see more of these assets forming part of relationship property pools or estates, on which lawyers will need to advise. This will become increasingly the case, as access to crypto as an investment and its use in commerce becomes more user friendly and frictionless.

Users

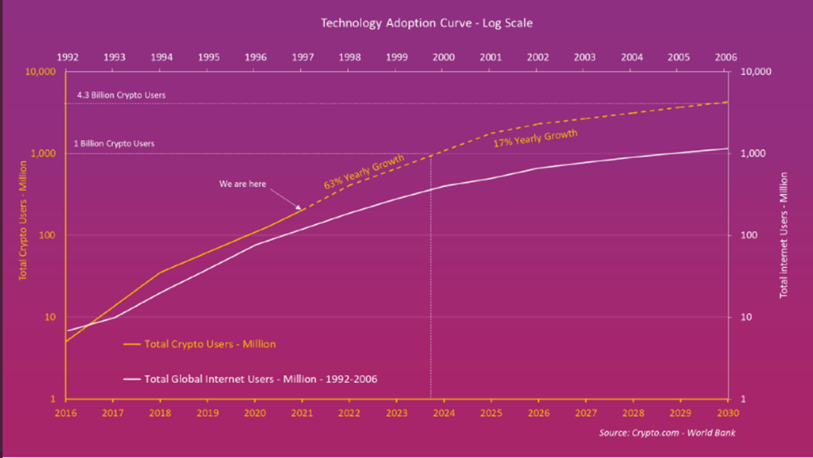

According to data from Crypto.com and World Bank, there are over 990 million crypto investors around the world, leading some to compare crypto’s adoption to that of other advanced technologies such as the internet, electricity and automobiles.[2]

Users are apparently growing at a rate of over 100% a year; this is well ahead of the adoption rates for the internet in the 1990s and early 2000s. Even if adoption rates slow down to 80%, crypto will still hit 1-billion users by 2024. That would mean one in every eight people on the planet will be interacting with crypto in some form.[3]

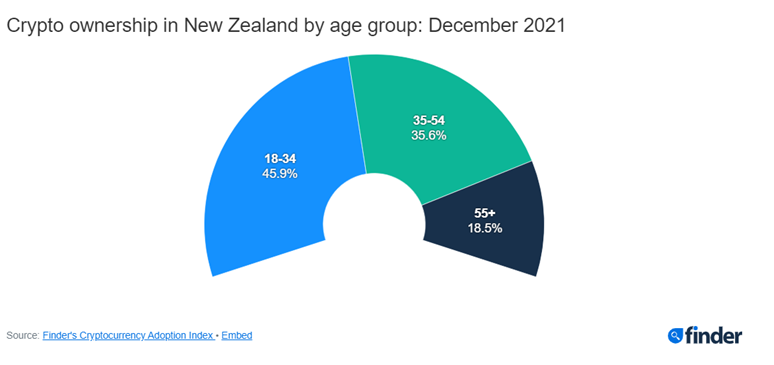

In late 2021, approximately 7.5% of the adult population in New Zealand was said to hold or have traded in crypto.[5] For Americans the figure is higher, with 16% saying they have invested in, traded or used crypto.[6] These percentages are set to increase, with younger “digital native” generations like Gen Z and Millennials displaying higher rates of adoption than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers. In New Zealand, those aged 18-34 dominate crypto ownership at 45.9%, while at 35.6%, 35–54-year-olds are the next most likely group to say they own crypto. Those aged 55+ come in last with 18.5%. [7]

In New Zealand, more men own crypto than women, with 21% of women saying they believe crypto is a good investment compared to 29% of men.[8]

Money invested

In recent years, crypto has solidified its status as a popular culture phenomenon as well as an investment strategy, albeit a risky one. Since July 2013, crypto’s market capitalisation has grown exponentially from just over $1 billion USD to just over $1.9 trillion USD in March 2022, peaking as high as $2.8 trillion USD in November 2021.[9] In terms of its use, in 2021, crypto’s most notable network, Bitcoin, settled $13.1 trillion USD worth of transactions. Bitcoin’s settlement volume surpassed Visa’s payments volume.

According to Fidelity, one of the world’s largest asset managers, interest in digital assets is growing. 49% of advisors have been asked about investing in crypto over the previous six months; 28% of advisors plan to increase their use or recommendation of crypto in the next year; and 71% of institutional investors surveyed globally expect to buy or invest in digital assets in the future.[10]

Disruptive innovation asset manager, Ark Invest, predicts that crypto and digital wallets will command nearly $50 trillion in equity market capitalisation by 2030. That would make the crypto market roughly 27 times larger than it currently is.

Recent eyewatering sale prices of crypto art have confirmed crypto as a new medium and class of assets in this traditional asset space. For example, digital artist Beeple’s ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’ sold for $69m USD via famous art auction house Christies, and digital images of celebrated New Zealand artist Charles Goldie sold for $127k at New Zealand’s first NFT auction via Webbs.[11] Such sales open a veritable ‘Pandora’s box’ for the estates and beneficiaries of artists, musicians, sportspeople, and other creatives who hold caches of intellectual property that can be digitised. It is no surprise that crypto businesses, like Glorious Digital, an NFT creative studio and marketplace, owned by former All Black Daniel Carter and former Solicitor-General Michael Heron QC, are popping up to meet local and international demand.

Institutional and nation-state adoption

As we discuss in our article on M&A – Legal Due Diligence and Crypto Assets, since the pandemic started in 2020, there has been a tidal wave of institutional interest from major financial and corporate institutions such as BNY Mellon, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Citi, Morgan Stanley, BlackRock, Mastercard, Square, MicroStrategy, Visa, PayPal and, most notably, Tesla which converted US$1.5 billion of its cash reserves into Bitcoin in January 2021.

Last year, El Salvador became the first nation-state to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender. President Nayib Bukele clearly sees Bitcoin as a means of dealing with his country’s reliance on the US Dollar, its economically crippling remittance problem, and to reduce the numbers of unbanked citizens. Six months on, the efficacy of that decision is still in issue. However, no one can deny its novelty or how the decision has made the world sit up and take notice of crypto.

Closer to home, the Kingdom of Tonga has received global media attention for its potential adoption of Bitcoin as legal tender. Like El Salvador, Tonga sees an opportunity to use Bitcoin to combat its remittance problem. It also plans to harness the country’s renewable and sustainable volcanic energy to mine the crypto.[12] While there is no suggestion at this point from our government that it would consider something similar, given Tonga’s proximity to New Zealand and our large Tongan population, what Tonga chooses to do will impact New Zealand.

Recently, USA President Joe Biden signed an executive order calling on the US government to examine the risks and benefits of crypto.[13] To quote a notable asset manager: [14]

“The top office of the most powerful country in the world felt a need to issue an Executive Order to outline a plan for studying cryptocurrencies / digital assets… It’s not a fad, it’s not a fraud, it’s not a Ponzi, it’s not going away, it’s technology.”

The European Parliament also recently paved the way for innovation-friendly crypto-regulation by voting for a uniform legal framework for crypto. This includes measures for consumer protection and safeguards against market manipulation and financial crime.[15]

The USA, like China and other countries, is exploring a digital version of the dollar or a ‘central bank digital currency’. Inevitably, what the US does with its law on crypto will impact on New Zealand law. We have already seen this with the development of our Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Act 2009, which places obligations on New Zealand’s financial institutions, casinos, virtual assets service providers, accountants, lawyers, conveyancers and high value dealers to detect and deter money laundering and terrorism financing.

As this paper is being typed, Ukraine became the latest country to legalise crypto.[16] Since Russia invaded Ukraine, more than $100m worth of crypto has been raised for the Ukrainian military defence.[17] This shows the power of crypto to be used for charitable and humanitarian purposes. Charitable and philanthropic ‘decentralised autonomous organisations’, or ‘DAOs’, such as Charity DAO and Big Green DAO, and traditional charities like Home & Family/Te Whare Manaaki Tangata, which are accepting crypto donations,[18] demonstrate how the technology can be used for good.

New Zealand’s Crypto Law Landscape

As crypto assets are relatively novel, the law surrounding their use and regulation is rapidly evolving. Like other governments around the world, our politicians are now trying to come to grips with the issues.

In 2021, our Parliament commenced an inquiry into crypto.[19] As our firm noted in our submission to the Inquiry (‘Inquiry Submission’), a key challenge is the ‘no knowledge’ or ‘lack of knowledge’ problem. It is easy for many to dismiss the utility of crypto, or be fearful of it, because of complexity. As it is relatively novel, technical, and rapidly evolving, there is, in general, a lack of education and understanding both for regulators and market participants. Parliamentarians, regulators, lawyers, accountants, financial advisers and journalists play a pivotal role as interpreters.

There might be a perception that crypto in New Zealand is not regulated, e.g. the FMA website guidance for investors in relation to crypto says:

“Cryptocurrencies are not legal tender (money that must be accepted as payment) in most countries and do not exist physically as notes and coins. They are also not viewed as financial products so are not regulated in New Zealand. There are over 4000 different cryptocurrencies available on the internet including Bitcoin, Ethereum and Litecoin to name a few.”

This could be accurate for truly decentralised protocols like Bitcoin, which have no centralised management or governance structure, such as a CEO, board of directors, or trustees, and it is true that there is no crypto-specific law. However, as we discuss in our Inquiry Submission, the reality is that there are many relevant New Zealand laws that apply to crypto investors and those building and operating crypto businesses in New Zealand. While crypto might not be legal tender, or physical currency, there is comprehensive regulation.[20]

Domestically and internationally, the Courts have now recognised that digital assets are property; however, as far as the writers are aware, only one case concerning crypto has reached our Family Court: Beck v Wilkerson.[21]

In 2020, in Ruscoe v Cryptopia,[22] a case concerning the insolvency of a failed Kiwi crypto exchange, our High Court determined that crypto is ‘property’ within the section 2 definition of the Companies Act 1993 (‘CA’) “and probably more generally”. It also concluded that, based on the facts of the case, the crypto in issue could be held on trust for individual investors, rather than company assets to be divided among a pool of creditors pari passu.

More recently, the UK Courts in Wang v Darby[23] considered the trust issue in the context of a contractual dispute. The Court did not need to determine whether the crypto in that case (Tezos) could be subject to a trust, as the parties accepted it could. However, the case includes some interesting observations suggesting that NFTs can be property subject to a constructive trust because of their unique or rare properties. It also demonstrates how crypto can concern litigation across jurisdictions, and how it can be the subject of not just injunctive relief, but that such relief can include worldwide freezing orders. Freezing orders covering crypto have been granted by our Courts in MB Technology Ltd v Ecomi Technology Pte Ltd.[24] In May 2019, Cryptopia’s liquidators also obtained urgent interim relief in US Courts as part of a petition for chapter 15 recognition of the New Zealand liquidation to preserve Cryptopia information stored and hosted on servers of an Arizona-based business.[25]

As we discuss below, Judge Ryan in Beck v Wilkerson accepted that the crypto in issue was “obviously relationship property assets”. Given the adoption trends discussed, we expect that this case is just the first of many. It is therefore critical that family and estates lawyers should remain alert to the issues associated with such assets.

What is Crypto?

A crypto asset is a digital currency, token, or non-tangible item, existing within computer networks and secured by cryptography. Cryptography is a form of internet security. It is the digital ability to anonymously and safely exchange messages on a network.[26] It is the process of turning information into code – encryption – so that only the intended recipient can access the information. Encrypting data protects information from would-be hackers.[27] Or, as Australia’s regulator ASIC has defined it:[28]

“a digital representation of value or contractual rights that can be transferred, stored or traded electronically. Crypto-assets use cryptography, distributed ledger technology or other technology to provide features such as security and pseudo-anonymity. A crypto-asset may or may not have identifiable economic features that reflects fundamental or intrinsic value.”

Categories of crypto

According to one site, there are currently over 13,000 types of crypto.[29] These take numerous forms. The authors of Blockchain Revolution posit seven categories (although these are not closed):[30]

- Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, XRP, Zcash and Dogecoin;

- Platforms or protocols like Ethereum, Cardano, Solana and Avalanche where the participants can carry out smart contracts;

- Applications that run on these networks, referred to as decentralized applications or ‘Dapps’;

- Security tokens which are used for representing equity in a company;

- Natural asset tokens (or commodity tokens), i.e. digital assets that have a corresponding physical asset;

- Crypto collectibles, e.g. NFTs like CryptoKitties, CryptoPunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club; and

- Crypto fiat currencies or ‘stablecoins’ which are pegged to a ‘fiat currency’ (a government-issued currency that is not backed by a physical commodity, such as gold or silver, but rather by the government that issued it) e.g. Tether is pegged to the US dollar.

Bitcoin and blockchain technology

The oldest, most well-known, and largest crypto by market cap, is Bitcoin. Before Bitcoin was created in 2008 by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto (the real identity of the creator is unknown), commerce on the internet relied almost exclusively on financial institutions as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. Such institutions maintain ‘centralised’ databases recording account balances.

Satoshi proposed an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust. This would allow two parties to contract with each other without the need for a trusted third-party intermediary. Satoshi’s white paper described a technology for creating a global, peer-to-peer currency that cannot be counterfeited, is not controlled by a single entity or group, and is protected from censorship, corruption and geographic limitations. There are no physical coins backing Bitcoin. It is an asset that exists only in digital form, but like cash, it does not require a central authority for settlement of transactions.[31]

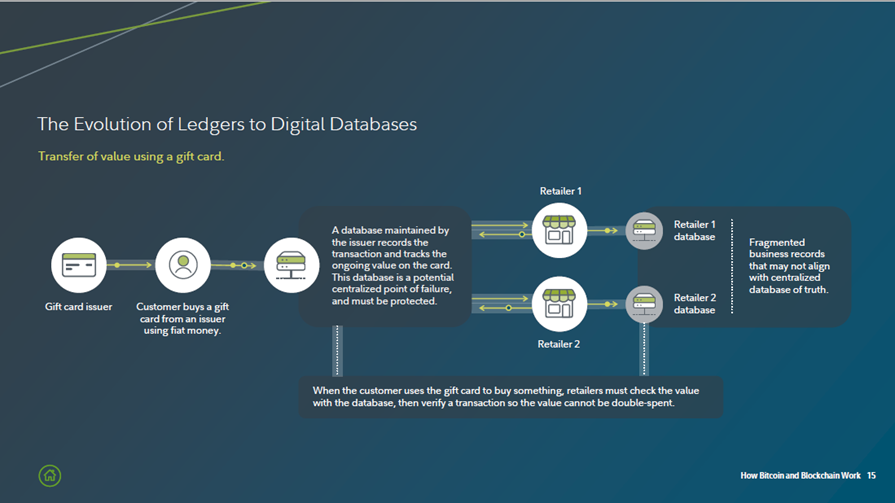

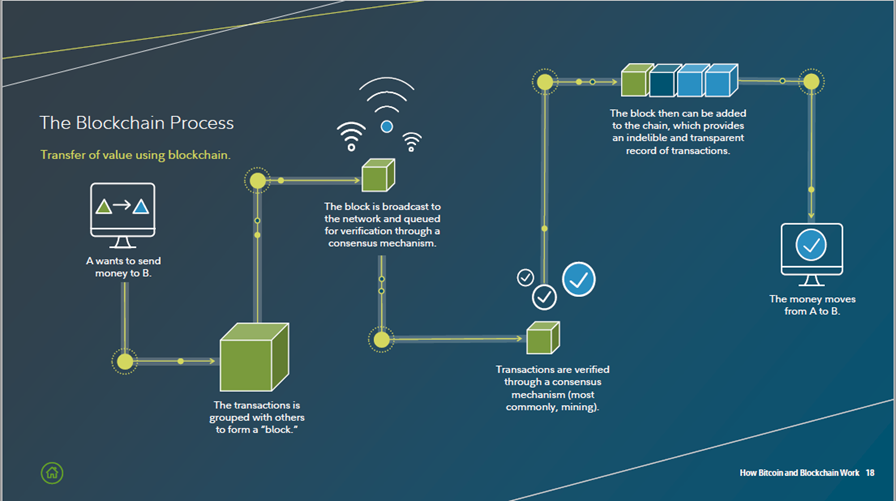

Crypto, such as Bitcoin, exists on a ‘distributed ledger’ or digital database called a blockchain which is verified by a ‘consensus network’ of computers. A blockchain is a chain of digital signatures verified by a peer-to-peer digital network. The blockchain records and maintains all transactions. It works effectively like triple entry accounting, with the computers in the network verifying that the ledger is correct. As new data comes in, it is entered into a fresh block. Once the block is filled with data, it is chained onto the previous block, which makes the data chained together in chronological order.[32]

The blockchain is ‘decentralised’ because no one party controls the network. Rather, all users collectively retain control. In a decentralised blockchain network, no one has to know or trust anyone else. Each member in the network (or ‘node’) has a copy of the exact same data. If a member’s ledger is altered or corrupted in any way, it will be rejected by the majority of the members in the network.[33]

Such a distributed and decentralised database solves the double spending problem (i.e. the risk that a digital currency can be spent twice).

It is useful to compare the traditional model for digital payments vs the blockchain process:

Each transaction which forms part of a block is timestamped. As each timestamped transaction is visible via a ‘block explorer’ [35] and the network constantly verifies the ledger of transactions, network participants can be confident that the blockchain represents an accurate record (right from the very first transaction).

Unlike some other protocols, the total number of Bitcoins is capped at 21 million (each divisible into 100 million ‘satoshis’); Bitcoin’s monetary policy is fixed. There will only ever be 21 million Bitcoins as this is baked into the code. This differs from fiat monetary policies, where central banks print more currency to stimulate economic growth, resulting in inflation. Bitcoin’s relative scarcity contributes to its value. To use a property analogy, there will only ever be 92km² of land on Waiheke Island; property titles can be made smaller, but the land available for building on is fixed.

However, as we discuss in our Inquiry Submission, because of the differing consensus mechanisms, not all protocols or tokens are created equally. Each consensus mechanism has its advantages and disadvantages. Bitcoin’s trade-off for being the most secure and decentralised protocol (and therefore arguably lower risk) is that the blocks are smaller, and less data is permitted at the base layer.

Other protocols with bigger block sizes, such as Solana, can handle more information / transactions and tend to be faster. However, these protocols may be less secure because of the increased potential for bugs in the code. They are also more prone to centralisation. ‘Proof of stake’ protocols (as opposed to Bitcoin’s ‘proof of work’ model) rely on users to stake their crypto to provide security to the network. These protocols may have environmental benefits but tend to be more centralised (and therefore more vulnerable to manipulation or coercion).

Bitcoin’s blockchain has famously never been hacked. Compare this, for example, to Poly Network, which is a newer protocol that recently suffered a significant security breach. The hack exploited a vulnerability in the way the protocol verified smart contracts which resulted in the theft of crypto worth about $600 million.

What are…niff-tees?

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are unique digital assets. By contrast, a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin is ‘fungible’ (i.e. each unit is equivalent to the next). NFTs can take numerous forms. To an uninformed observer, NFTs could be seen as nothing more than overpriced jpegs, but that is to oversimplify them and understate their potential value.

NFTs can be a digital image, like the artworks of New Zealand-born Samoan artist Iokapeta Magele-Suamasi:

Or NFTs can be part of a collection, more like baseball collector cards or comic books. The creator can ‘mint’ a range of different forms of digital media (e.g. picture, video, photo, audio) and can build in a continuing royalty. In art terms, an NFT offers provenance via the publicly searchable blockchain.

NFTs have a range of use cases, from artwork, collectibles, sports, gaming, entertainment, identity verification, to real estate and finance. NFTs offer a unique entertainment experience for promoters, musicians, brands, sports teams and their fans. They can be not only tickets or digital merchandise, but also a unique opportunity to own and trade memories and reward fan engagement. For example, California music and arts festival, Coachella, recently announced that it was releasing a collection of NFTs which offered onsite perks and VIP access.

According to Binance Academy:

“NFTs have the potential to be one of the key components of a new blockchain-powered digital economy. They could be used in many different fields, such as video games, digital identity, licensing, certificates, or fine art – and even allow fractional ownership of items. Storing ownership and identification data on the blockchain would increase data integrity and privacy, while easy, trustless transfers and management of these assets could reduce friction in trade and the global economy.”

Due to their variability, NFTs present unique challenges for lawyers. In some respects, they can look like simple products, like an artwork or music file. In other cases, they can look more like financial products potentially subject to our Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013. For example, the goal of Vesta Equity is to allow homeowners to tap into the equity in their homes through tokenization. According to the company, token holders would then be able to sell off a portion of it as a fractionalized NFT.[36]

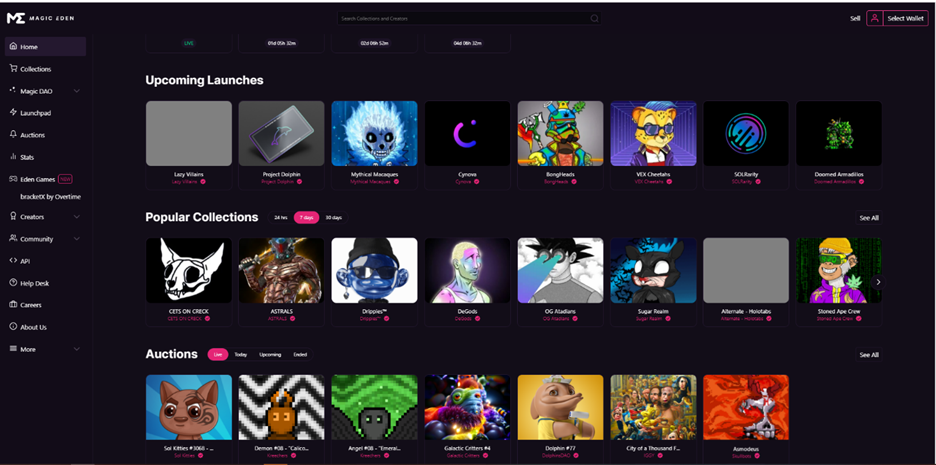

This article from The Spinoff provides a useful breakdown of what they are, how they work, and where to buy them (e.g. marketplaces such as Opensea and MagicEden). New Zealand NFT projects such as Flufs and Pixelmon have featured recently in news media, the latter for being comically bad despite raising over $100m.

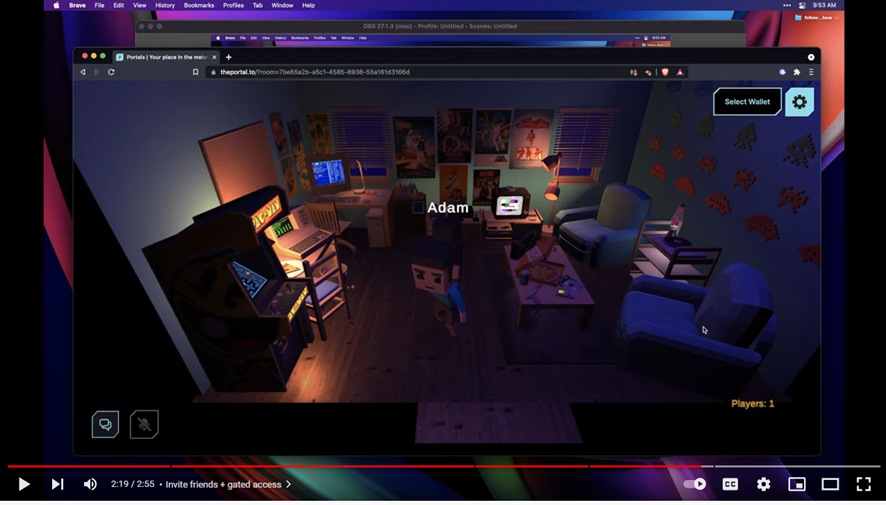

Far from being limited to just personal profile pics or ‘PFPs’, NFTs are also becoming a gateway to the metaverse. For example, Portals, which is an NFT built on Solana, allows a holder to own digital real estate within the Solana metaverse, where they can build out unique spaces to conduct meetings (a bit like Zoom) and display their other NFTs.

Far from being limited to just personal profile pics or ‘PFPs’, NFTs are also becoming a gateway to the metaverse. For example, Portals, which is an NFT built on Solana, allows a holder to own digital real estate within the Solana metaverse, where they can build out unique spaces to conduct meetings (a bit like Zoom) and display their other NFTs.

Play-to-earn games

NFTs and play-to-earn games highlight the growing market demand for and interrelationship between crypto and gaming. Games such as Axie Infinity allow digital artworks and collectibles to be ‘minted’ (i.e. included in a block) by the content creators, used in the game, and traded (similar to stocks) in crypto markets. According to this video, children as young as 12 are making a living playing Axie Infinity. During the pandemic, countries like the Philippines saw large scale adoption as people used the game to supplement their income.[37] ‘Gamefi’ shows the potential for people of all ages to own and trade crypto and for there to be such assets within relationship property pools and estates that might not have previously been considered.

Logistics

Crypto assets can be purchased through various platforms. Firstly, a user needs to convert NZD to their chosen crypto. This can be done through specialised currency-to-crypto exchanges or ‘VASP’s, like Easy Crypto, Dasset, and Independent Reserve.

From the exchange, the crypto can then be transferred to a ‘wallet’ for retention or transacting. Wallets can be either ‘hot’ or ‘cold’. A hot wallet is connected to the internet and can be accessed via mobile or desktop apps. Cold wallets are not connected to the internet and are usually in the form of a USB-style device. Wallets operate a bit like bank accounts: receiving, storing, or transferring a user’s digital assets.

Wallets are accessed by the user with ‘keys’.[38] A ‘public key’, also referred to as a ‘public address’, allows someone to receive crypto transactions. Think of a public key like your bank account number. It’s a cryptographic code that is paired to a ‘private key’. While anyone can send transactions to the public key, you need the private key to ‘unlock’ the wallet to transfer the crypto.[39] Think of the private key a bit like your internet banking password or the front door key to your house. If a user loses the private key to their wallet, e.g. through mismanagement or a cyberhacker, the user usually loses access to their wallet and the assets within entirely. Unlike a bank though, if you lose your private key, users are unable to request a new one. The assets remain on the blockchain, but the user cannot access them.

Some wallets are ‘custodial’ (i.e. a third party such as an exchange like Coinbase or Binance manages the private keys), while others are ‘non-custodial’ (the user is responsible for securing their private keys, like Ledger or Trust Wallet).While the former might be more convenient because it negates the need for personal private key security, it presents different types of risk, e.g. counterparty insolvency, confiscation, or hacking risk.

While NFTs can be traded peer-to-peer, and some exchanges like Binance and FTX are now also offering them, most NFT trading occurs on specialised websites. For example, the biggest site for Ethereum NFTs is Opensea, while Magic Eden is the most recognised marketplace for Solana NFTs. These platforms operate like TradeMe or Facebook Marketplace. In some cases, platforms or wallets will allow the purchase of crypto via credit card.

The Property (Relationships) Act 1976 – Classification

The High Court in Ruscoe v Cryptopia[40] made a number of important statements, which will likely be relevant if questions arise in the family law or estate context. As previously stated in this paper, the Court noted that the cryptocurrencies held within Cryptopia’s exchange were property within the section 2 definition of the CA, “and probably more generally”. It also found that cryptocurrency met the required characteristics of ‘property’ to be defined as such, being: definable; identifiable by third parties; capable in its nature of assumption by third parties; and having some degree of permanence or stability.

- The Property (Relationships) Act 1976 (‘PRA’) broadly defines ‘property’ within section 2 as:

- real property;

- personal property;

- any estate or interest in any real property or personal property;

- any debt or any thing in action;

- any other right or interest.

The wide definition given to ‘property’ under the PRA is similar to various other statutes in New Zealand,[41] and its interpretation and application has only extended over time. Its distinction from the meaning of ‘property’ under the Property Law Act 2007 was considered in Clayton v Clayton:[42]

“The Property Law Act definition is: ‘everything that is capable of being owned, whether it is real or personal property, and whether it is tangible or intangible property’. This is an attempt to define what the concept ‘property’ means, unlike the definition in the PRA which is essentially an inclusive definition, with, arguably, an extension of the normal concept of property to include a ‘right’ or an ‘interest’, even if it is not a right or interest in property.”

In the writers’ view, it is without doubt that crypto and NFTs sit comfortably within the definition in section 2 of the PRA.[43] Subparagraph (e) leaves significant room for the inclusion of less traditional or conventional assets. Given how varied crypto can be, it could be captured by b), c),[44] and potentially d) of section 2 of the PRA also.[45] Likewise, section 2 will also catch other intangible rights or interests, such as those in NFTs.[46]

To the writers’ knowledge, Beck v Wilkerson is the only reported case in New Zealand under the PRA that has dealt with this issue in respect of crypto, though only at the family court level. Whilst the Court did not undertake any assessment of the position, nor was it asked to do so. It dealt with a crypto known as Litecoin like all other property for division in that case (and made orders under the PRA in respect of that asset accordingly) – seemingly without pause or question.[47]

Needless to say, in the context of a relationship, the pertinent issue will be whether any such ‘property’ is in fact ‘relationship property’ (as was the crypto in the case of Beck v Wilkerson, it having been acquired during the parties’ relationship) having regard to section 8 and other relevant provisions in the PRA, which is an altogether different question. The corollary of this will go beyond the obvious fact that the crypto will then comprise the relationship property pool susceptible for division; it could also then become the subject of an application for various interim orders under section 25, including for an interim distribution or sale, or it could form part of an order under section 15.

Potential Issues and Complications

Identification – Locating the crypto

As there are several thousands of different types of crypto, all of which can be held and regulated (or not) in a variety of ways and in different places,[48] this can pose enormous complications for a party (and ultimately too their lawyer) when attempting to identify the relationship property for division. Unlike real estate or shares, for example, there is not a centralised service or system (like LINZ or the Companies Register) which can be searched to identify, by name,[49] the owner(s) of a crypto asset (if you even know one exists).

The anonymity afforded by crypto platforms, and the intangible nature of digital assets, may create hurdles for a client who has been excluded from financial decisions during the relationship and has little knowledge of the property in play. On top of that, some crypto has been engineered to be difficult to detect. Suffice to say, this landscape provides fertile ground for one spouse/partner to hold assets without the knowledge, visibility or accessibility of the other – which should really come as no surprise, given the meaning of ‘crypto’ – ‘concealed’; ‘secret’.

From an estate administration point of view, issues could arise where a will does not provide specifics to enable the executor to locate the crypto to realise and distribute them.

As crypto continues to increase in prominence and expansion, so too will the likelihood that such assets are held by clients. It is therefore wise to be alert to the potential existence of digital assets at the commencement of your inquiries with them.[50] It may be that when you send your initial letter to the other party or their counsel listing the assets (and liabilities) to your and your client’s knowledge, that when you put the general question as to whether there are any other assets which the other party owns or in which they have an interest, it is expressly and specifically queried as to whether crypto assets exist.[51]

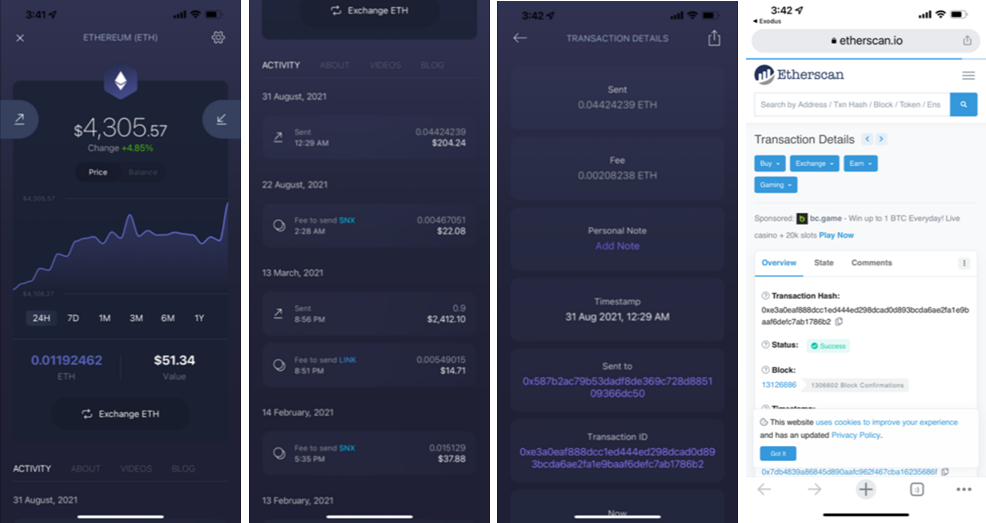

If the other party holding crypto is forthcoming in the disclosure process, naturally this should not be an issue. Details of any and all holdings should be sought, and blockchain may then be used to independently substantiate that information (e.g. the wallet address(es) provided by that party). Exchanges, wallets and NFT marketplaces have records of transactions and activity and the party holding the crypto should be able to access that information from their platform. Most of these platforms enable a downloadable copy of the user’s transaction history. These are viewable like bank statements and can be used to verify the holdings.[52]

In the above example, you can see the transaction details for the Ethereum (ETH) sent from the user’s Exodus wallet on 31 August 2021. By clicking on the ‘Transaction ID’, this will take you to the Etherscan ‘block explorer’. The transaction details also show you the ‘public key’ address to which the ETH was sent.

Transactions undertaken by exchanges are also often followed up with an email to the holder. The emails usually record the date, time and value of the transaction. Provision of emails may assist in identifying or verifying the extent of the relationship property pool.

Difficulties will inevitably be encountered when a party refuses to cooperate in the disclosure process or is actively concealing these assets. If it is suspected that crypto is held but has not been disclosed, wholly or in part (i.e. they have disclosed some, but your client has suspicions there are more), a good place to start will be retrieving and considering relevant bank statements (that is, if they are not also being withheld). As discussed earlier in this paper, to acquire crypto, often a user is required to transfer NZD to an exchange. Alternatively, a platform may allow crypto to be purchased with a credit card – all of which will leave a trail in such statements. When reviewing bank transactions, lawyers should look out for any large unexplained transactions, or transactions to unknown recipients, in the usual way. In respect of the latter, a simple Google search of the recipient of the funds could show that funds have been moved to a registered crypto exchange. When and if this is identified, (more targeted) questions can be asked of the party responsible for the bank transaction and/or the recipient. Needless to say, if it is suspected that crypto may be held by a company,[53] careful attention should be paid to the financial statements (in particular, the asset schedules) of such companies.

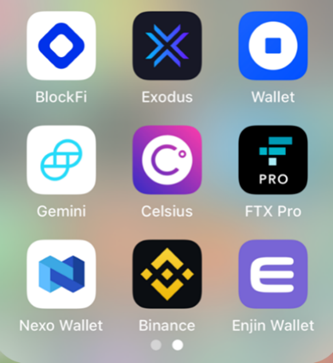

Another (lateral) means of gaining information could include seeking disclosure of the applications on the holder’s mobile phone. Different crypto platforms and exchanges have phone applications for accessibility and use and, if obtained, clients should be asked whether they recognise such applications. This could swiftly discern whether crypto assets exist. The applications in the example below include non-custodial wallets, centralised exchanges, and centralised finance or ‘CeFi‘ platforms.

Other places which could provide relevant information are social media sites. Most NFT launches occur via Twitter, Discord and Telegram. If the client is aware of particular holdings, reviewing these platforms for user engagement could reveal helpful information.

Due to the transparency of blockchain, with information like transaction IDs which are identifiable on blockchain explorers like Blockchair,[54] blockchain forensics tools and companies like Elliptic, Chainalysis and Ciphertrace are a burgeoning service. There are also a handful of ‘crypto sleuths’ on Twitter like @zachxbt who expose bad actors in return for donations.

In the unfortunate event that the above avenues lead you nowhere, your client may wish to seek discovery by invoking the usual formal court processes. However, it must be remembered that this remedy is limited to the production of documents only and cannot be utilised as a ‘fishing expedition.’ If an application for discovery[55] is not available (where proceedings are not afoot or in the case where a notice of defence has not been filed), a pre-proceedings application for discovery may be considered (before you embark on substantive litigation[56]).

Other avenues which may be of help here, in the context of litigation, could be serving the other party with a notice to produce documents,[57] notice to admit facts,[58] or a notice to answer interrogatories[59] (situation dependent). The types of documents sought, or questions asked, may centre around the information mentioned above. Certainly, such information is in the holder’s possession, power and control. Indeed, similar methods could be contemplated if crypto assets have been disclosed in proceedings but require independent verification (to which one party does not have access). The Inland Revenue Department could also lend some assistance.[60]

In the (albeit unlikely nowadays) event that digital assets are purchased from someone using cash, it may not be possible for such assets to ever be identified.

Valuation – When and how?

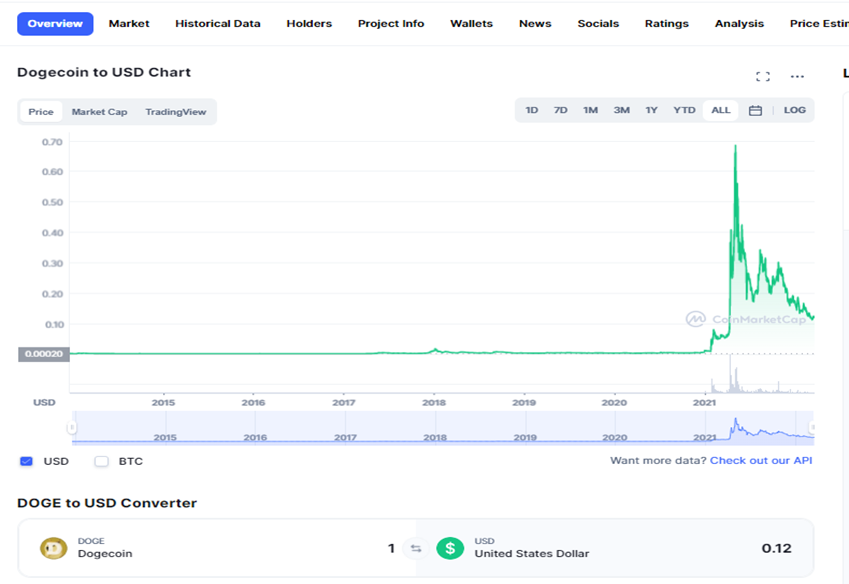

Digital assets tend to be subject to great volatility and uncertainty, as they are a new and evolving technology. As the value of crypto is generally dependent on people’s future expectations or outlook of the price in the future, informed by its popularity and in some cases its exclusivity or scarcity,[61] changes in value can occur dramatically, regularly, and instantly, based on market conditions.[62] In this way, the value of these assets is a moving target and can shift considerably in minutes and, indeed, will have done so while you have been reading this paper

The fluctuating nature of the price and value of these digital assets, and the extent to which it can be ‘news flow driven’, is further illuminated by the following ‘real’ examples:

It cannot be disputed that Twitter comments by Elon Musk, entrepreneur and

co-founder of Tesla, contributed to Bitcoin price volatility when, in early 2021, he announced that Tesla would be accepting Bitcoin as a form of payment, only to say months later that the company would no longer be doing so, citing concerns in respect of its environment impact and sustainability. This created a sudden surge and then sudden decrease in its value. However, Elon Musk has since said that Tesla will ‘most likely’ start accepting the digital currency as payment again in the future once the percentage of renewable energy usage is most likely at or above 50%, and that there is a trend towards increasing that number (which again gave rise to a corresponding appreciation in value).[63]

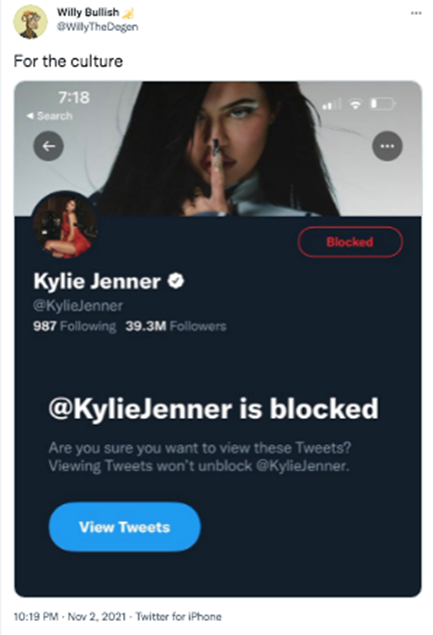

Socialite and reality TV star, Kylie Jenner, privately expressed her interest to a ‘Bored Ape Yacht Club’ (‘BAYC’) owner in buying one of the NFTs, but the offer was rejected, and she was famously ‘blocked’ on Twitter by the NFT owner. Ms Jenner made her displeasure known on social media and, owing to her worldwide recognition and popularity, this led to a temporary dive in the floor value of the collection.[64] This is hardly surprising when she was considered to be (at least in part) responsible for a plunge of more than a billion dollars in the value of Snapchat shares after she made an unfavourable comment about the application on Twitter.[65]

However, since then the floor price of BAYC has grown exponentially in value, with other stars such as Justin Bieber acquiring the NFTs.[66]

While as lawyers we must be conscious not to be (or be perceived as) offering financial advice we are not qualified to give, being aware of the volatility of crypto in general terms is important as it may impact on your client’s strategy.

Valuing crypto or NFTs in a relationship property context raises two key issues:

- When do you take the value?

- How do you ascertain value?

The most desirable time for attributing a value will naturally depend on who you are acting for and the division of assets contemplated (i.e. if your client is to retain the crypto and purchase the other party’s share, and its value is skyrocketing, they will be motivated to ‘lock in’ a value at pace, whereas if you are acting for the other party in that situation, ascribing a value at a later date, or even deferring/postponing division of the asset, will be far more attractive).

Section 2G(1) of the PRA dictates the appropriate date for valuation. It provides a general rule that the value of any property is to be determined as at the date of hearing of the application by the Court of first instance. In a negotiation context where proceedings have not been filed, this will be its current market value. However, there is a built-in discretion for a Court decide that the value of the property is to be determined at another date under section 2G(2), which is customarily exercised in favour of a date of separation value where assets are of a depreciating kind or where one spouse/partner has sole control over the use and disposition of the asset.[67]

To the writers’ knowledge, there have been no reported cases in New Zealand which have determined the time at which crypto or NFTs should be determined.[68] The timing and method of valuation was not (and could not be) considered in Beck v Wilkerson[69] as the wallets holding the Litecoins were moved from laptops and hard drives to an iPhone, which could not be found. In those circumstances, the presiding judge could do no more than make an order declaring that if the wallets could be accessed by either one of the parties, that the Litecoins are jointly and equally owned by each party.[70] No value could be identified or realised as the electronic wallets were unable to be located and accessed.

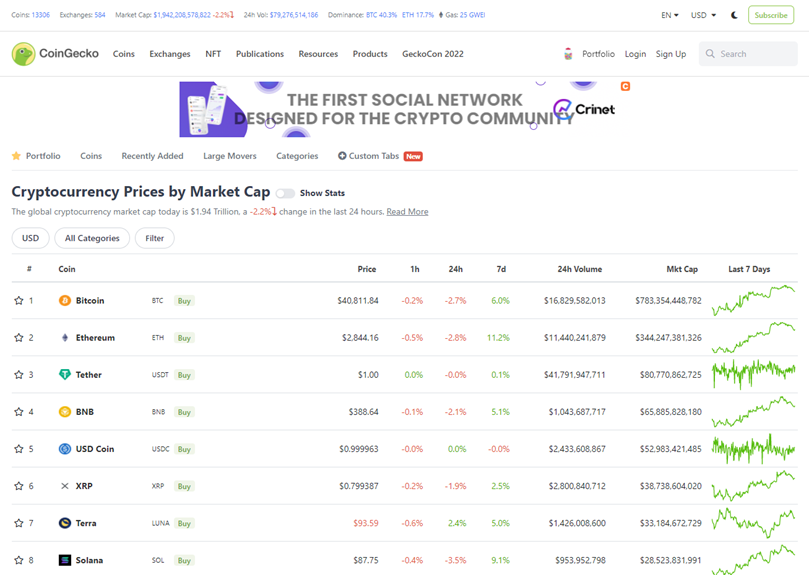

From a practical point of view, determining the value of listed tokens is easy enough. It is not necessary to source a formal valuation as this information is publicly available (much like publicly listed shares). CoinGecko and Coinmarketcap are examples of sites that track market prices and offer other helpful information in a digestible way.

Valuing NFTs is trickier, however. Unlike fungible crypto like Bitcoin which is very ‘liquid’ (i.e. able to be transferred easily), because NFTs are unique, they are potentially very ‘illiquid’ (i.e. cannot be transferred easily). This brings risk if, for example, there was to be a market correction and funds were to flow out of crypto into other asset classes (e.g. cash or treasury bonds). In such a case there may be no market for the NFT at all.

Often the value of an NFT is linked to its rarity. Generally, the rarer an NFT, the more valuable it is. Determining rarity will therefore be key to determining the value. Websites such as howrare.is, moonrank, and cryptoslam can assist in this process. The ‘floor’ price for an NFT collection on a given marketplace will represent the lowest value the market is willing to pay for an NFT in that collection, but you must be aware that different marketplaces can have different floors. NFT value can also be influenced by the protocol it is minted on (e.g. Ethereum or Solana).

One should not assume that because one NFT looks like another, its value will be similar. By way of example, the Ethereum ‘Bored Ape Yacht Club # 5575’ below left recently sold for 128.82100 ETH or $376,015.29 USD[71] while the Solana ‘Bored Ape Solana Club #3095’ below right was recently listed on MagicEden for 0.4 SOL, or around $36.00 USD.[72]

Division on Separation

Plainly, crypto can[73] and should be included in agreements under section 21A of the PRA, akin to any other relationship or separate property.

Generally speaking, where such assets are relationship property for division, the parties may choose to distribute these assets in one of the following ways (which are not mutually exclusive; a combination could be adopted):

- The crypto and/or NFT(s) are liquidated and the proceeds divided equally between the parties (in NZD) – in which case the parties should be cognisant of the tax implications, as discussed elsewhere in this paper.

- One party retains some or all of the crypto and/or NFT(s) and compensates the other for their value – where one party has been the one to acquire and control these assets, this may be the most sensible option, provided the value can be agreed upon (and that practically, that party can afford to purchase the other’s share, or it is sufficiently recognised in the division of other property).

- The crypto and/or NFT(s) are retained in their current form (as digital assets) by both parties, shared equally between them – most likely in cases where they both have familiarity, experience and, of course, an enduring interest in holding such digital assets. It may be the case that one party is confident in this market and comfortable with its volatility, but that the other has had little to do with the investment and is risk averse – in which case this option would be ill advised. If this option is elected, and both parties do not (already) have their own existing wallets, one party will need to set one up. The parties should also consider a ‘multi-sig’ wallet which requires the private keys of two or more parties to transfer the crypto.

Other matters which fall for consideration include:

- In New Zealand, digital assets cannot be (at least not yet) cashed out at an ATM. They can, however, be converted from crypto back to NZD via an exchange. In so doing, there will be additional costs, just as there are when real property or shares are liquidated. Such costs may include exchange charges and tax.[74] When considering the options (which will include liquidating the asset) and weighing up the outcomes of different scenarios for division, such costs should be factored into the equation. Foreign exchange rates should also be considered, where applicable. Advice should be obtained from a specialist about (precisely) what any exchange or tax implications may mean for your client.

- Where the value of the crypto held is especially volatile (perhaps determined by factors such as how new it is and so on) and is rising and/or falling frequently during negotiations/proceedings, and it is intended that the asset is to be retained by one party, the parties may wish to identify and monitor its value at different times, and come to a median figure (in a similar way to when parties obtain a number of different registered valuations or appraisals for real estate and agree to determine the value as being the figure in the middle). This would go some way in addressing the risk of inequality in division if the party keeping the crypto is left with an asset which subsequently skyrockets or plummets in value, particularly if settlement or the implementation of orders does not take place immediately.[75] Another idea could be to add a formula to an agreement to provide that, for example, if the market value increases by a certain percentage, there will be a corresponding change in the way other assets are divided.

- It is wise to question the best means for holding digital assets pending the resolution of matters and a section 21A agreement being executed (or proceedings determined). This is especially so in cases with a high level of conflict and distrust and/or when digital assets comprise a large part of the property pool. In such situations, you and your client will need to be alive to the possibility that there may be (or have been) a disposition of digital assets. This is particularly so because of the ease and speed with which an owner of crypto and/or NFTs can transact with anyone, anywhere – the world is your marketplace, operating 24 hours a day. If the asset is held solely by the other party:

- It would be advisable to seek an undertaking from them that it will remain untouched or appropriated, unless or until otherwise agreed by both parties. Otherwise, it could be transferred to another person whilst matters are being resolved;

- The parties could agree to transfer the crypto to a multi-sig wallet;

- If the client knows the public address of crypto held on a cold wallet, a ‘watch-only wallet’ app could be used to monitor if assets are being transferred;[76]

- The usual options for recourse would of course apply, where a disposition intending to defeat the relationship property rights of a spouse/partner is imminent[77] or has occurred.[78] Likewise, if a disposition has been made to a qualifying company or trust;[79]

- It is perhaps worth noting that where crypto is held in a wallet or via an exchange, a party will need the password to access and handle the assets.

- It may be preferable, in circumstances like those referred to above, to exchange the volatile and/or potentially vulnerable assets to NZD. Then, the funds can be held in a solicitors’ trust account on the basis that the usual undertakings are given that they remain undisbursed absent agreement or a Court order (and placed on interest bearing deposit if they so wish) until settlement. This would also remove a highly volatile product from the hands of one party (if held by one only). In the alternative, the crypto could be transferred to a more stable form, such as an NZD stablecoin like NZDS, or a USD stablecoin like Tether. Both options could better ensure fairness. However, again, the tax implications will need to be considered, as converting one crypto to another could give rise to a taxable event.

- The party who does not hold the assets should take steps to make certain that they are kept safe and protected, such as ensuring that passwords or wallet keys are not lost. Lawyers should be wary of any request from a client to take custody of keys or other such items on their behalf.

- If digital assets, which are the relationship property of both parties, have materially diminished in value as a result of the action or inaction of one spouse/partner after their relationship has ended, section 18C may offer some relief, though it must be remembered that any such action or inaction must be shown to be deliberate for this provision to bite.

- In Beck v Wilkerson, there were competing accusations as to what had become of the Litecoins and the respondent sought a compensatory award in their favour against the applicant pursuant to section 18C.[80] It was argued that the applicant was directly responsible for either the loss of the iPhone, or the disappearance of the laptop and hard drives, on which the electronic wallets were stored and, by failing to report this to police and/or to take steps to ascertain where they may be, the applicant was responsible for a deliberate inaction. Ultimately the claim failed because the presiding judge was not satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that the decision not to report the missing items was a deliberate inaction on the part of the applicant designed to diminish the value of the relationship property pool (which would equally impact the applicant herself).

- It is important to account for future ongoing benefits arising from owning NFTs (e.g. the party retaining that asset might have continuing benefits like further airdropped assets or a share of collection resale royalties). How this is done is fact specific and could be very challenging without an intimate knowledge of the project.

Contracting Out under Section 21

More often, as crypto becomes more commonplace, family lawyers can expect clients to seek to “ring-fence” such investments acquired pre-relationship as their separate property, to which their spouse/partner shall have no claim in future.

When including crypto in a contracting out agreement, there should be as many details as possible, including the specific number of units, tokens or coins held, how they are held, any public key addresses, and their identified value at the time of the agreement, so that there can be no argument later that this was not known or understood. Where the wording ‘at the time of this agreement’ (and not as at a particular date proximate to signing) is used, given the dynamic nature of crypto, lawyers will need to ensure that this is revised and updated where the agreement is executed sometime after it was initially prepared and subsequent drafts circulated. This process can span weeks or months, particularly where the matter is complex or discord develops, and revision will ensure accuracy (as much as is possible). This will of course be true, too, for section 21A agreements.

It will be important to be clear whether the client wishes to protect the current holding itself (whatever its value at the end of a relationship), its current market value (in NZD),[81] or so too its increase in value. It will also be important to establish whether it is anticipated that further contributions (which may involve the application of relationship property) will be made during the currency of the relationship and, if so, whether those are also to be protected.[82] If that is not intended, but eventuates, a comprehensive agreement will dictate the consequence of that.

As already noted, the parties may wish to consider whether they also want to create a wallet in their joint names via multi-sig and have that clearly defined in the agreement as relationship property, as part of the methods by which they are able to acquire property jointly going forward.

In the case of NFTs, it will be important to include any derivative benefits or rights relating to the NFT as separate property.[83]

Other Resources

If you would like to learn more, there are countless books and other materials available online.

- BlockchainNZ, a leading New Zealand organisation, has an Info Hub with a wealth of educational resource.

- EasyCrypto and Binance Academy also have helpful educational resources.

- This podcast by New Zealand Financial Adviser, Victoria Harris and media personality Sophie Hallwright, Raising The Curve https://thecurve.co.nz/pages/podcasts, provides a useful beginner overview from a female perspective in an easily digestible conversational format.

Useful books include:

- Blockchain Revolution by Don and Alex Tapscott;

- The Internet of Money series by Andreas Antonopoulos;

- The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking by Dr.Saifedean Ammous;

- Layered Money by Nik Bhatia;

- Inventing Bitcoin by Yan Pritzker;

- Bubble or Revolution? by Neel Mehta, Adi Agashe and Partha Detroja;

- The Infinite Machine by Camila Russo;

- The Messari annual crypto thesis is also excellent.

Disclaimer

This paper is not intended as legal advice and it should not be considered or relied on by any reader as such. Like most aspects of law, each crypto legal issue must be considered by reference to its own facts. Stace Hammond do not profess to be experts in any other field discussed in this paper, e.g. economics, financial advice, accounting. The article should not be treated as professional advice of any kind (e.g. legal, accounting, tax, or financial advice). It is for educational purposes only. Please note that the material linked in the article is for illustrative purposes only. Its inclusion is intended to make the paper accessible for all readers, not just lawyers. Except for our own web articles, Stace Hammond does not necessarily agree with or endorse the statements made in the linked material. We reference it for its overall usefulness for this discourse. Stace Hammond does not claim any copyright or other intellectual property rights in those linked works. We also reserve the right to correct any errors in the paper that we discover. In the interests of disclosure, some Stace Hammond partners hold a range of crypto investments across a range of platforms. Such crypto investments include tokens / projects referenced in this paper. We see involvement in crypto in this manner as critical to our own education and understanding so we can best serve our clients.

[1] A definition of crypto and its forms begins at paragraph 4 of this paper.

[2] https://www.outlookindia.com/business/crypto-adoption-rate-similar-to-1990s-internet-boom-says-wells-fargo-report-news-121823

[3] https://mg.co.za/special-reports/2022-01-25-crypto-in-2022-from-crypto-adoption-outpacing-the-internet-to-which-sectors-are-worth-watching-out-for-and-everything-in-between/#:~:text=Cryptocurrency%20users%20are%20growing%20at,1%2Dbillion%20users%20by%202024

[4] https://twitter.com/raoulgmi/status/1392939136689053699?lang=en

[5] https://thespinoff.co.nz/business/15-10-2021/as-finance-company-memories-fade-a-new-generation-of-investor-is-shooting-for-the-moon

[6] https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/11/16-of-americans-say-they-have-ever-invested-in-traded-or-used-cryptocurrency/

[7] https://www.finder.com/nz/finder-cryptocurrency-adoption-index#:~:text=In%20New%20Zealand%2C%20those%20aged,come%20in%20last%20with%2018.5%25.

[8] https://www.finder.com/nz/finder-cryptocurrency-adoption-index#:~:text=In%20New%20Zealand%2C%20those%20aged,come%20in%20last%20with%2018.5%25.

[9] https://coinmarketcap.com/charts/

[10] Fidelity Institutional Insights, Bitcoin and Digital Assets, Understanding the Digital Ecosystem: https://institutional.fidelity.com/app/proxy/content?literatureURL=/9903921.PDF

Fidelity Digital Assets is a division of Fidelity Investments. Fidelity has $4.5 trillion in assets under management as of December 2022 and assets under administration of $11.8 trillion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fidelity_Investments

[11] https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/460726/digital-images-of-goldie-sell-for-127k-at-new-zealand-s-first-nft-auction ; https://www.webbs.co.nz/news/nfts/

[12] https://news.bitcoin.com/kingdom-of-tonga-may-adopt-bitcoin-as-legal-tender-says-former-member-of-parliament/

[13] https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/09/heres-whats-in-bidens-executive-order-on-crypto.html

[14] Mark Yusko, chief investment officer and managing director of Morgan Creek Capital Management, at 4:06 https://youtu.be/XrsiXOEUJXc

[15] https://twitter.com/blocktelligent/status/1504136054424870917?s=21

[16] https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/17/ukraine-legalizes-cryptocurrency-sector-as-donations-pour-in.html

[17] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/19/bitcoin-to-the-rescue-cryptocurrencies-role-in-ukraine

[18] For more see this article: https://theconversation.com/cryptocurrency-funded-groups-called-daos-are-becoming-charities-here-are-some-issues-to-watch-174763

[19] https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/technology/2021/07/nz-government-launched-cryptocurrency-inquiry-to-understand-benefits-and-risks.html; https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/make-a-submission/document/53SCFE_SCF_INQ_111968/inquiry-into-the-current-and-future-nature-impact-and

[20] For further discussion of the key acts that can apply to crypto, please see section 6.1 of our Inquiry Submission.

[21] Beck v Wilkerson [2019] NZFC 9883; [2020] NZFLR 342.

[22] Ruscoe v Cryptopia Ltd (in Liq) [2020] 2 NZLR 809. We discuss the case in greater detail in our article What To Do If A Cryptocurrency Business Goes Bust

[23] Wang v Darby [2021] EWHC 3054 (Comm) (17 November 2021) https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2021/3054.html

[24] MB Technology Ltd v Ecomi Technology Pte Ltd [2020] NZHC 2883.

[25] https://www.grantthornton.co.nz/globalassets/1.-member-firms/new-zealand/pdfs/cryptopia/second-liquidators-report-to-creditors_cryptopia.pdf

[26] For more information:

https://www.investopedia.com/tech/explaining-crypto-cryptocurrency/#:~:text=The%20%22Crypto%22%20in%20Cryptography,-The%20word%20%E2%80%9Ccrypto&text=%22Cryptography%22%20means%20%22secret%20writing,ensure%20pseudo%2D%20or%20full%20anonymity.

[27] https://blockgeeks.com/guides/blockchain-cryptography/

[28] https://asic.gov.au/media/cmvhlkeg/selectcommitteeausfintechcent-asic-submission-july-2021.pdf

[29] https://www.coingecko.com/

[30] Don Tapscott and Alex Tapscott, Blockchain Revolution, 2016 and 2018, Penguin Random House UK.

[31] Fidelity Institutional Insights, Bitcoin and Digital Assets, Understanding the Digital Ecosystem: https://institutional.fidelity.com/app/proxy/content?literatureURL=/9903921.PDF

[32] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/blockchain.asp

[33] https://aws.amazon.com/blockchain/decentralization-in-blockchain/#:~:text=In%20a%20decentralized%20blockchain%20network,the%20members%20in%20the%20network

[34] Fidelity Institutional Insights, Bitcoin and Digital Assets, Understanding the Digital Ecosystem: https://institutional.fidelity.com/app/proxy/content?literatureURL=/9903921.PDF

[35] For example https://etherscan.io/ , https://blockstream.info/ , https://solscan.io/

[36] https://cointelegraph.com/news/nfts-and-defi-are-revolutionizing-real-estate-investing-and-homeownership-here-s-how

[37] https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/14/people-in-philippines-earn-cryptocurrency-playing-nft-video-game-axie-infinity.html

[38] Also often with a password or other form of two-factor authentication.

[39] https://www.gemini.com/cryptopedia/public-private-keys-cryptography#section-what-is-a-public-key

[40] Cryptopia above

[41] Including the Family Proceedings Act 1980, Child Support Act 1991 and Crimes Act 1961.

[42] Clayton v Clayton [2016] NZSC 29, [2016] 1 NZLR 551, (2016) 31 FRNZ 61 at [27].

[43] Indeed, the New Zealand Law Commission considered this to be the case when it examined whether the PRA definition of ‘property’ could accommodate ‘new and emerging’ property such as virtual currencies in its October 2017 – Dividing relationship property – time for change? Issues Paper 41, page 150 at 8.16 and 8.17.

[44] Relevantly, the definition of ‘personal property’ in section 16 of the Personal Property Securities Act 1999 includes: ‘documents of title’, ‘goods’, ‘intangibles’, ‘investment securities’, and ‘money’.

[45] Personal Property Securities Act 1999, s 16.

[46] In this regard, the expansive interpretation of ‘property’ in the recent case of Palmer v Alalaakkola [2021] NZHC 2330, in which both the Family Court and the High Court found that copyright in paintings was ‘property’ under the PRA, is noted. The older case of Dixon v R [2015] NZSC 147, [2016] 1 NZLR 678 is also noted, whereby the Supreme Court held that video footage, namely CCTV footage, fit within the definition of ‘property’ in section 249 of the Crimes Act 1961 (which as earlier mentioned defines ‘property’ in a similar way to the PRA).

[47] His Honour Judge Ryan stated “I accept the submission of course that the Litecoins are part of the property pool” at [40] and “The Litecoins are obviously relationship property assets” at [13].

[48] Held in a hot wallet, a cold wallet ‘offline’, or via a centralised exchange and so on – as discussed elsewhere in this paper. The asset may also be made up of several transactions over several years.

[49] Wallet public addresses are visible on the blockchain, but their owners’ names are not.

[50] Essentially, add it to your ‘checklist’ or similar when you run through the property in existence with your client.

[51] Lawyers should be warned against making any assumptions about whether a party is likely (or not) to hold such assets. Various research and studies have shown that people of all ages and backgrounds have invested and continue to invest in these assets, including thousands of New Zealanders. Certainly, though, where a party has spent time in a country with a distrusted or unregulated banking system or without a centralised or governing body or institution at all, this should be increasingly on your radar. Or equally, where a party is or has been involved in regular foreign transactions (and may wish to avoid the delay, fees and forms involved in doing so through the bank).

[52] Such statements will show the balance of the holding, its transaction history and so on.

[53] Noting that recent data has shown that companies are increasingly diversifying their assets to include those of a digital nature.

[54] www.blockchair.com. This engine describes its aim as becoming the Google for blockchains.

[55] Under rule 141, Family Court Rules 2022.

[56] Under rule 140, Family Court Rules 2022.

[57] Rule 153, Family Court Rules 2002.

[58] Rule 138, Family Court Rules 2022.

[59] Rule 137, Family Court Rules 2022.

[60] The IRD should have records of transactions through New Zealand centralised exchanges (most of which are VASPs and required to be registered Financial Service Providers and AML compliant) and this may provide another avenue for discovery.

[61] Such as in the case of Bitcoin, where there is only a limited number that will ever be available.

[62] Noting that unlike other stock markets which have trading hours, the crypto market is constantly moving and responding to world events (which can sometimes lead to an “overreaction” in the crypto market).

[63] https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/tesla-will-most-likely-restart-accepting-bitcoin-payments-says-musk-2021-07-21/

[64] https://nfthours.com/an-nft-manifesto-on-kylie-jenner-being-blocked-over-a-bayc/

[65] The value of these digital assets has attracted attention and controversy in various other instances in pop culture. For example, some celebrities, including Kim Kardashian, have been accused of being involved in a ‘pump and dump scam’, whereby they were allegedly used by the creators of EthereumMax, or EMAX, to endorse and promote the (then) new cryptocurrency in order to inflate its price, after which their holdings were sold for substantial profit. Jimmy Fallon also came under criticism this year, 2022, when he shared his BAYC token on his show, The Tonight Show, as did a celebrity appearing on the show (Paris Hilton), which was regarded by many as a conflict of interest (by using the platform of the show to elevate its asking price if he was to sell it).

[66] https://www.coingecko.com/en/nft/bored-ape-yacht-club

[67] As such, the prevailing approach is for household chattels and motor vehicles to be valued in this way.

[68] Indeed, the case of new technology or digital assets such as cryptocurrencies, where “best practices for valuing [such] emerging forms of property not have developed”, was identified by the Law Commission as posing difficulty in its review of the PRA in October 2017: Dividing relationship property – time for change? Issues Paper 41, page 151 at 8.21.

[69] Beck v Wilkerson above.

[70] “The judge further ordered that the parties were to “continue to use their best endeavours to gain access to the digital wallets in which the Litecoins are held. If either party or their agent at any time is able to access the Litecoins, in whole or in part, they are to notify forthwith the other party and provide that party with all the information they hold and to appoint a stakeholder to attend to all that is necessary to maximise the value to the two parties and to realise the sale or other disposition for value of the Litecoins.”

[71] https://cryptoslam.io/bored-ape-yacht-club/mint/5575/

[72] https://magiceden.io/item-details/7BC5fnW3phiABjRgetc2gzN3KP1ShYRGvq5KzoXZFJUg

[73] Section 21D, PRA.

[74] It is clear that these assets are regarded by the IRD as property for tax purposes. For further information about taxation of crypto please see our articles on this topic, including: https://stacehammond.co.nz/new-zealand-tax-treatment-of-crypto-assets/ and https://stacehammond.co.nz/new-zealand-tax-treatment-of-crypto-assets-for-business/. Also see the IRD’s website for more information: https://www.ird.govt.nz/cryptoassets

[75] It may be that the agreement simply states that the party who is to retain the asset shall account to the other as to 50% of its value on the settlement date. Certainly, if the intention is for the asset to be liquidated at some time after an agreement is signed, a percentage should be used.

[76] For example https://bluewallet.io/watch-only/

[77] Section 43, PRA.

[78] Section 44, PRA.

[79] Sections 44F and 44C, PRA.

[80] Beck v Wilkerson above. Here, the applicant accused the respondent, her brother, or possibly her current partner, as being responsible for the theft of the Litecoins in the wallets. For the respondent’s part, she accused the applicant of having cashed in the Litecoins, using the proceeds to acquire drugs and alcohol and for the purposes of international travel.

[81] Though the possibility of the value decreasing instead will need to be carefully considered.

[82] Being mindful of section 9A of the PRA.

[83] I.e. that any income or gains earned from the asset will be that party’s separate property.

Subscribe

Get insights sent direct to your email.